“I will give thanks unto God while I have my being” (from a sampler sewn by a different Jane Austen, a combination of verses from various Psalms)

“Let us come before his presence with thanksgiving . . .” (from Psalm 95, read daily in the Morning Prayer service of the Book of Common Prayer)

Happy Thanksgiving! In the United States, while Thanksgiving is based on the Pilgrims’ celebration back in 1621, it was first celebrated as a nationwide holiday in 1789 (when Jane Austen was 13) to give thanks for the end of the American Revolution, following a long British tradition of holidays whose focus is on giving thanks to God for national blessings. It did not become a yearly national holiday until the 1860s. Canada has their own Thanksgiving, the second Monday in October.

Great Britain does not have a national holiday for Thanksgiving. They do celebrate a Harvest Festival in late September or early October, around the end of the harvest season. This Festival has ancient roots, but only became a regular church celebration in the Victorian era, well after Austen’s time.

However, in Austen’s Church of England, every church service included thanksgiving. The Book of Common Prayer (1760) says one of the purposes of the worship service is “to render thanks for the great benefits that we have received at his hands . . .”. It also prescribes prayers specifically for “Thanksgivings”: one of General Thanksgiving for God’s goodness and loving kindness, others for rain, fair weather, plenty, peace and deliverance from enemies, restoring public peace at home, and two prayers for deliverance from plague or sickness.

National Days of Thanksgiving

The English government also decreed national holidays focused on God. Occasional days were prescribed for fasting and prayer (“fasting and humiliation”) for national needs, usually on Wednesdays. Joyful events were celebrated on designated days of Thanksgiving with prescribed church services. Some events, including the birth of a new prince or princess and some military victories, were simply celebrated with a special prayer of Thanksgiving (published by the government) for Sunday or daily prayer services. But other events called for holidays of nationwide Thanksgiving, usually on Thursdays. Some of these are recorded in the diaries of country clergymen in Austen’s England.

On Thursday, April 23, 1789 (the year of America’s first national Thanksgiving), Parson Woodforde reads Thanksgiving prayers at his church, with many people attending: “This being a Day of public thanksgiving to Almighty God for his late great mercies to our good and gracious King George the third, in restoring him to Health after so dangerous an illness . . .”. The king and both houses of Parliament went to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London in a grand procession “to return thanks.” Woodforde adds, “It is to be a great day of rejoicing every where almost. We heard the firing of Guns from many Quarters about Noon.”

The day chosen is marked in the Prayer Book as the Saint’s Day for “St. George, Martyr,” so was appropriate for King George. The service published for the occasion includes Scripture readings expressing thankfulness for God’s deliverance and healing (Psalms 34 and 103, and Isaiah 12) and an admonishment to submit to rulers and authorities (Romans 13). Prayers offer general thanksgiving and specific thanks for the king’s healing and blessings on all of his family. A Communion Service is also prescribed.

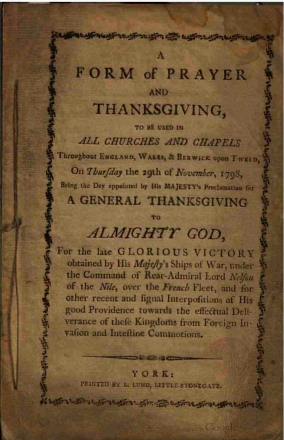

On a later Thursday, Nov. 29, 1798, Parson Woodforde writes, “Great Rejoicings . . . today on Lord Nelsons late great & noble Victory over the French near Alexandria in Egypt. An Ox roasted whole in the Market-Place &c. This being a day of general Thanksgiving Mr. Cotman read Prayers this Morning at Weston-Church, proper on the Occasion.”

The verses and readings in this prayer service focus on God’s power and on obedience to Him. The prayers give thanks for victory and pray for the protection of Britain’s naval fleet, reminding all to be thankful since any victory is from God. Finally a “Prayer of Thanksgiving for the Plenty of the Year” echoes our own Thanksgiving: “O Merciful Father, of whose gift it cometh that the earth is fruitful, and animals multiply for the service and sustenance of man; we give thee humble thanks, that, of thy great bounty thou hast crowned the year with thy goodness; causing both the sun to shine, and the rain to fall, in just measure and due season, and blessing the increase of our kine [cows] and of our sheep. — Continue, we beseech thee, thy loving kindness towards us, and give us grace to improve thy mercies to thy glory, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.” (“Improve” here means to make good use of; God gives us mercies, and we use them in ways that glorify Him.)

Woodforde also celebrates by giving his servants “strong-beer and some Punch” after dinner to drink to the health of Nelson and his officers and sailors. Many Nelson souvenirs were produced at this time, some including laurel. A laurel wreath is a symbol of victory, dating from ancient Greece. A contemporary dance was even entitled, “Sprigs of Laurel for Lord Nelson.”

Another country parson, William Holland, records a similar Thanksgiving service for another victory led by Admiral Nelson on Thursday, Dec. 5, 1805: “this is the Thanksgiving Day for Lord Nelson’s Glorious Victory. . . I ordered Laurel to be put on the gate . . . In a short time most of the Parish had Laurel in their hats and the Church was adorned with Laurel. I read the Prayers sent by the Government.” Holland rode to his second church and, since “there is no printed Afternoon service sent I converted the Morning Service to Afternoon to them. . . . Our Bells were ringing all this day and Illuminations [lights or decorations made from candles and lanterns] were ordered.” He and his friends enjoyed a special dinner and supper. The town was decorated for the occasion with transparencies [greased prints on lanterns or in front of candles] related to the victory, and they had “Squibs and Crackers” [fireworks]. It sounds like the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving rolled into one!

Some Thanksgiving services were held on a regular date each year, such as the date the Sovereign ascended the throne. On Thursday, November 5, 1812, and Sunday, November 5, 1815, Holland records “The Ringing of the Bells” (the church bells) waking him in the morning; it was the yearly Thanksgiving day for the Discovery of Guy Fawkes. Guy Fawkes was the head of the “Gunpowder Plot” to blow up Parliament in 1605, in an attempt to replace King James I with a Catholic king. The plot was uncovered and foiled early on Nov. 5. The Book of Common Prayer includes a whole church service, “Gunpowder Treason,” to be read on Nov. 5 each year, Guy Fawkes’ Day, which is still a day for bonfires and fireworks.

A number of other Thanksgiving services and celebrations were held during Austen’s lifetime for political events and events in the royal family. Thanksgivings celebrated the end of the war with France, twice: On Thursday, July 7, 1814, and on Thursday, Jan. 18, 1816. Napoleon was exiled to Elba in the spring of 1814, but escaped early in 1815 to be defeated again at Waterloo. Austen’s novel Persuasion is set in the time period in between, when the war seemed to have ended, which is why its hero Captain Wentworth is ashore; the return of war is foreshadowed at the end of the novel.

While she didn’t have a yearly Thanksgiving holiday in November, Jane Austen would have celebrated “Thanksgivings” fairly often during her lifetime, as well as giving thanks each time she read daily prayers.

In each of these Thanksgivings people gathered to praise and thank God together, as well as celebrating in other ways. What gifts and mercies are you thankful for this November? May you have a very thankful Thanksgiving!

Sources

Paupers & Pig Killers: The Diary of William Holland, A Somerset Parson 1799-1818, edited by Jack Ayres, Sutton Publishing 1984, pages 122-123, 241, 308.

The Diary of a Country Parson 1758-1802, James Woodforde, Oxford University Press 1978, pages 348-9, 570.

You can watch the dance “Sprigs of Laurel for Lord Nelson.” Note that a couple stands out for awhile at one end of the dancers, then at the other end (each couple in turn). This was common in Austen-era dances, and was probably when most of the conversation while dancing that Austen describes occurred.

Love this, thanks for sharing

LikeLike

You’re very welcome! Thanks for dropping by.

LikeLike